How a UFC Impostor Became Australia's First NHB Event

This is the final installment of a multi-part series on the

first modern MMA show held in Australia, billed the “Australasian

Ultimate Fighting Championship.”

PROLOGUE |

PART 1 |

PART 2 |

PART 3 |

PART 4 |

PART 5

Within minutes of the great Mario Sperry

beating Chris

Haseman to win the “Australasian Ultimate Fighting

Championship,” the eight-sided cage was brimming with drummers and

dancers in celebration of the 30-year-old Brazilian’s victory.

As 5,000 spectators slowly filed out of the Darling Harbor Exhibition and Convention Center into Sydney, a prime “Ze Mario” was overcome with pride, relief and the sensation that he “fought with a thousand cats.” Sperry had scratches all over his body due to a painted canvas that “was like sandpaper.” He wanted to surf the Australian waves the next day, but it was too uncomfortable to get in the water.

“I was so drained,” Bable said. “My wife had three or four or five too many to drink in the VIP area during the fights. I just remember the drive back over the [Sydney] Harbor Bridge and her having to put her head out of the taxi window. You know, a bit of stress was involved from her side, too.”

With their combat obligations discharged, the fighters and their entourages let loose on Sydney. By all accounts, the camaraderie flowed as freely as the beer. Frank Shamrock ended up on a boat dancing and drinking with the Brazilians; Elvis Sinosic played tour guide for the Lion’s Den crew, taking them to some of Sydney’s nightclubs; and Neil Bodycote’s team put down a few schooners with Zane Frazier, whom he replaced in the tournament, along with other members of Sperry’s entourage. There was a strong sense of kinship among men charting a new frontier.

“It was a very small world,” Shamrock said. “These are guys that you train with, live with, travel with. The Brazilian groups were always very welcoming and family-oriented, so when we met Mario, it was kind of the same vibe. Even though we were standing opposite each other, it just felt good. We were all doing the same thing. We’re in a foreign country doing our thing.”

* * *

The morning after the event, Bable was up early arranging for fight purses to be paid via bank transfer from revenue the event had generated. Next came tearing down the infrastructure built inside the convention center. Lastly, he made sure he had all the footage of the spectacle ready for post-production.

Bable’s to-do list grew that Wednesday when SEG filed proceedings against him for trademark infringement, arguing he had passed off his promotion as the UFC and unlawfully used SEG’s logos and intellectual property.

Among other things, the lawsuit sought to temporarily restrain Bable from distributing the event on VHS (this, after he had already peddled pre-sale orders through Blitz magazine) and to prevent him from marketing the tournament and future events as the “Australasian UFC.” In addition, SEG sought damages with interest, compensation for legal costs, orders that Bable publish corrective advertising and orders that permanently prevented Bable from using an octagonal cage in future NHB events.

Ultimately, SEG appeared to lose interest in the lawsuit after Bable gave a legal undertaking to the Federal Court to change the name of the event to “Caged Combat 1” and include disclaimers stating it was not associated with or licensed by SEG. The release of the VHS was delayed some weeks as a result of the proceedings, but by mid-April, he was free to distribute it in hopes of making back at least some of the estimated $250,000 he invested in the tournament.

* * *

It was at this point that Bable believes he made a fatal error.

“I got a deal,” Bable said. “Lionsgate Films picked up the rights to actually distribute it, as did Warner Bros. Lionsgate bought it and shelved it, for whatever reason. I think that may have had something to do with the SEG. When I followed up and asked, ‘Why isn’t this happening?’ The response I got was that they wanted to promote the UFC brand and shelve my VHS because they wanted to invest in the UFC. They wanted to buy the rights to distribute in this area.”

That left Time Warner as an option, according to Bable, but it was not meant to be. This was the moment that played a key role in the demise of his fight promotion and his decision to leave the industry.

“I had the music from the ‘Fever Girls,’ which we didn’t have the rights for,” Bable said. “The post-production guy said they could lay in some studio music. We could have done it right then. I said ‘hold on’ and called my copyright attorney. I explained the situation. We didn’t have rights to one of the songs; it was a Bon Jovi song from memory. I said that we could edit it out right now and asked what we should do. The advice was, ‘Don’t worry about it. It won’t be a problem.’ That advice totally killed everything that I did. The music rights stopped everything.

“We tried negotiations directly. They did as well with Bon Jovi,” he added. “We were negotiating and trying to get these rights, because we didn’t want to go back to post-production. And then it just ... it was an impasse. I think Time Warner actually sent me a letter saying if we couldn’t reach it by a certain time, they would have to drop it—and they did.”

* * *

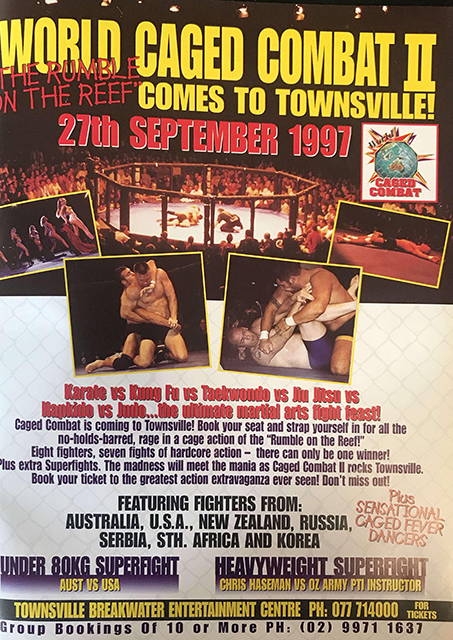

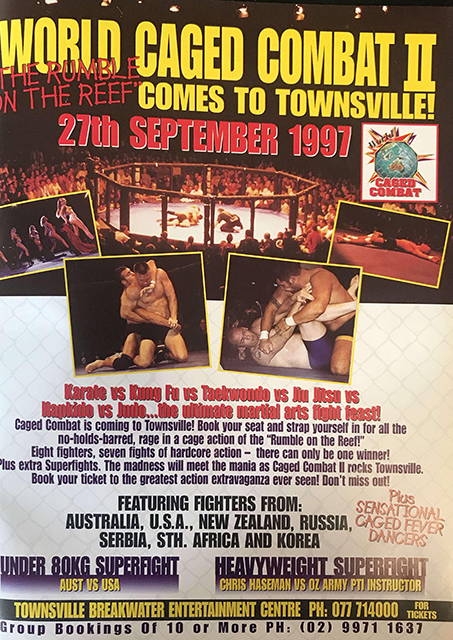

Bable persisted with his original vision well into 1997. Full-page advertisements for “Caged Combat 2: The Rumble on the Reef” were placed in multiple issues of Blitz magazine published in the second half of the year.

A partial lineup of combatants included original tournament participants Chris Haseman and Elvis Sinosic, UFC veteran Paul Varelans, three-time Olympic wrestling alternate Tom Erikson and Australian Pancrase fighters Larry Papadopolous and Alex Cook.

The format was the same—an eight-man elimination tournament as the primary showcase—and two single-bout “superfights.” However, the planned event never came to fruition.

An advertisement for “Caged Combat 2:

The Rumble in the Reef,” set to take

place near the Townsville Army Barracks

in Queensland on Sept. 27, 1997.

With Bable struggling for cash as a result of

disappointing video sales following the first event—his only avenue

for distribution was through Blitz magazine and later on a

custom-made website—he pushed back the date of Caged Combat 2 and

organized a smaller card billed as “Australian

Vale Tudo.” The event, scheduled for November 1997, was held at

Whitlam Leisure Center in Liverpool, New South Wales, in front of a

couple thousand spectators.

The fights took place on a rectangular canvas reminiscent of a traditional boxing ring but with chain-link fence instead of the ropes. Sinosic’s trainer, Anthony Lange, fought at the event and broke his arm after he fell back onto the chain link.

“Because the chain has no give, it’s basically a steel bar when it’s taut.” said Sinosic, who fought and won twice that night. “An interesting thing I heard through the grapevine, and I put this together after the event: Randy didn’t pay everyone. One of the [contractors] who wasn’t paid was [one of] the people who put the cage together. So for the Australasian Vale Tudo event, they didn’t have a cage.”

Though rumors swirled regarding Bable dishonoring his contracts with suppliers, only one, referee Cameron Quinn, confirmed being stiffed.

“Tell Bable he still owes me $300,” Quinn said.

Bable denied that he left any contractor high and dry.

“Everybody got paid,” he responded. “Although there were a few people that probably took longer to get paid than they should have.”

There’s little doubt that finances were a big reason why he downgraded for the AVT event and left the industry all together soon after.

* * *

Bable’s contribution, short lived as it was, was nonetheless important to the people who shared the experience.

Michael Schiavello got his start in MMA commentary thanks to Bable.

“I had one in the books. I had done a solid job. I had a calling card. I would go on to commentate MMA events worldwide and work on the big promotions such as Strikeforce and Dream and Dynamite and One Championship,” Schiavello said. “It all began with Caged Combat, and I will forever be grateful for Randy Bable giving a 22-year-old an opportunity to commentate a major event in the history of Australian martial arts.”

Chris Haseman and Elvis Sinosic, virtual unknowns in 1997, received significantly greater exposure on the international stage from the event. Sinosic took Frank Shamrock to a decision at the K-1 Grand Prix 2000 Final event three years later, then made his way into the UFC, where he fought for the 205-pound title against Tito Ortiz. Haseman would fight his next 25 fights for Japan’s Rings organization, culminating in a bout with Fedor Emelianenko in 2002.

Even controversy from their fight served to be a positive for the pair. Sinosic criticized Haseman for his alleged dirty tactics, cementing a rivalry that bubbled in the background while they represented Australia on the international circuit. Some 13 years after their first meeting, the UFC touched down in Australia for the first time with UFC 110 at Sydney’s Acer Arena, and a rematch was booked for the two past-their-prime pioneers. The fight would ultimately fall through—Sinosic was forced out with a shoulder injury, and Haseman was removed from the card—but the spotlight certainly did not hurt them as they transitioned into retirement.

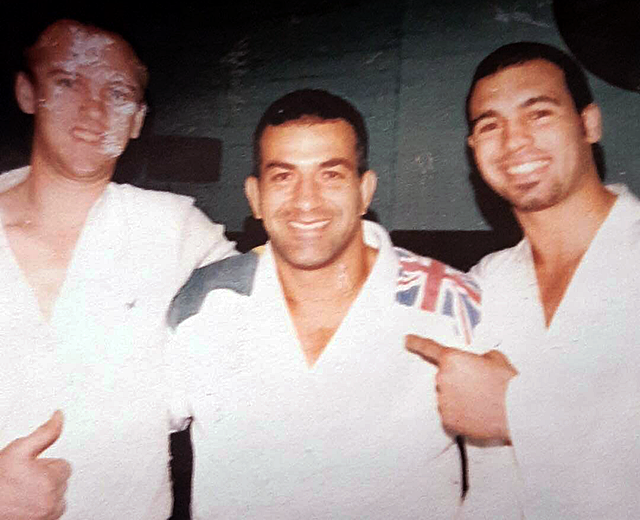

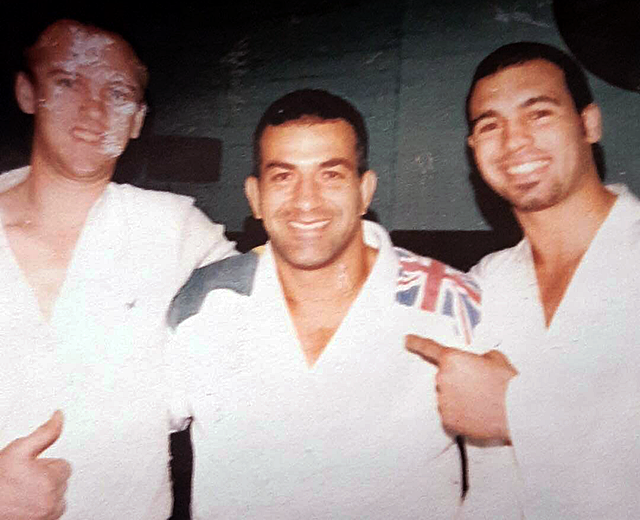

Neil Bodycote, Mario Sperry and Elvis

Sinosic, all smiles during Sperry’s

BJJ seminar in Sydney.

The remaining three ANZACs—Simon Sweet,

Hiriwa Te

Rangi and Neil Bodycote—experienced less decorated careers. Te

Rangi would continue competing in MMA, but his professional record

stands at 2-9, and he is mostly remembered for kickboxing. Sweet

never competed again in mixed fighting, and

the only remnants of his kickboxing career are a handful of YouTube

videos from the mid-1990s. Bodycote, the first Australian to

compete in a modern mixed-rules bout on his home soil, competed

once more in NHB, picking up a victory at Bable’s Australian Vale

Tudo event. Tragically, he took his own life in 1998.

Vernon White claims his participation in the “rip-off” UFC event led to SEG refusing to work with him, though he eventually signed with the promotion after it had been purchased by Zuffa in the early 2000s. Matt Rocca, whose debut fight against Sinosic lasted all of 41 seconds, also had a tough time returning to the Lion’s Den and departed the academy soon after.

“I was a disaster,” Rocca said of the aftermath of his trip to Australia. “Keep in mind that this was an extremely successful team. They’re all alphas. If you do well, you’ll get the accolades. If you don’t, you’ll hear about it. That wore on me. Although I had competed, I didn’t make that transition from young boy to fighter.”

Rocca returned home to Canada, dejected with his performance, holding onto the sense that the MMA industry was not going to “take flight.” Time spent away from the fight game made the 20-year-old reconsider what he wanted to do with his life. He had a revelation: “Maybe this was not what I was destined to do.” Rocca listened to his parents, who advised him to go to school. Today he is a police officer in Ontario, Canada.

* * *

Perspectives differ on what impact, if any, that Bable and his short-lived promotion had on mixed martial arts, in general, and on Australian MMA, in particular.

For his part, Bable likes to think the scale and professionalism of his spectacle on March 22, 1997 set a high-water mark for NHB at the time and played a part in propelling the sport into the multibillion-dollar industry it is today. Others lament that the promotion was too ahead of its time to meaningfully influence the trajectory of NHB, which was about to disappear from cable television in the United States and spend years languishing in relative obscurity outside of Japan.

The dearth of major events in Australia until the real UFC touched down in 2010 supports the latter interpretation of history. Though small promotions, including incarnations of Pancrase and Rings, tried cultivating a market for mixed fighting in Australia in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was not until later that a reliable regional scene established itself. This was followed by a trickle of Australian fighters into the UFC and other organizations—“The Ultimate Fighter” Season 6 semifinalist George Sotiropoulos and Bellator MMA middleweight champion Hector Lombard were among them—but the region’s talent did not explode until the UFC targeted Australia for regular events, including with its biggest stars, and a handful of seasons of “The Ultimate Fighter.”

Australia and New Zealand have since produced contenders across multiple divisions and crowned three UFC champions: Robert Whittaker, Alexander Volkanovski and Israel Adesanya. Australian crowds twice set the attendance records for UFC events—first at UFC 157, where Holly Holm shocked the world by knocking out the seemingly indestructible Ronda Rousey with a second-round head kick, and next at UFC 243, where Adesanya, the current 185-pound champion, commenced his championship run with a stunning knockout of Whittaker. Australia is frequently cited as the UFC’s biggest per-capita PPV domain, and ever more Australian fighters and organizations are being brought within the promotion’s orbit.

How much credit Bable deserves is a matter for debate.

“I just ran out of steam,” Bable said. “You look at the event and everything that happened. Everyone—everyone—tried to stop me. I was up against the wall every direction I went. The police, the boxing commission, the local government. The venues didn’t want us, the sponsors didn’t want us. In the end, we made a great product, but everybody tried to stop us. I got beat down for a year, then took a bath on the income, as well. I had to recover from that.

“I basically just got back to work,” he added. “I was a commercial builder, so I went back to putting together contracts. I fortunately had the ability to do that, but it took a little while to recover. I had a wife and two little kids, remember. If I was a single man, it might have been a different story, but my family was my top priority.”

Aware of the opportunity he had in 1997 to impact the direction of MMA, Bable thinks about what could have happened if not for a few bad calls—with Renee Rivkin or the distribution deal with Time Warner.

“It would have changed the course of my life,” he said. “It tormented the hell out of me for five years, you know?”

Bable was coy when asked if he was completely over MMA. He wrote a screenplay inspired by the March 1997 event and plans on releasing the second vale tudo event at some point. The raw footage is gathering dust in the Tennessee home where he currently lives with his wife.

Jacob Debets is a lawyer and writer from Melbourne, Australia. He is currently writing a book analyzing the economics and politics of the MMA industry. You can view more of his writing at jacobdebets.com.

Advertisement

AFTERGLOW AND UNREALIZED POTENTIAL

As 5,000 spectators slowly filed out of the Darling Harbor Exhibition and Convention Center into Sydney, a prime “Ze Mario” was overcome with pride, relief and the sensation that he “fought with a thousand cats.” Sperry had scratches all over his body due to a painted canvas that “was like sandpaper.” He wanted to surf the Australian waves the next day, but it was too uncomfortable to get in the water.

Pulling off the event gave Randy Bable one of the biggest

adrenaline rushes of his life, but he had been scraped up by the

experience, as well. Bable had to circumnavigate Semaphore

Entertainment Group’s threats to shut down the event with an

injunction for trademark infringement. He talked down the Boxing

Authority of New South Wales and more than 20 uniformed police

officers who threatened to storm the cage and pull fans from the

bleachers. An hour and a half after it was all over, he and his

wife returned home feeling like a huge weight had been lifted from

their shoulders.

“I was so drained,” Bable said. “My wife had three or four or five too many to drink in the VIP area during the fights. I just remember the drive back over the [Sydney] Harbor Bridge and her having to put her head out of the taxi window. You know, a bit of stress was involved from her side, too.”

With their combat obligations discharged, the fighters and their entourages let loose on Sydney. By all accounts, the camaraderie flowed as freely as the beer. Frank Shamrock ended up on a boat dancing and drinking with the Brazilians; Elvis Sinosic played tour guide for the Lion’s Den crew, taking them to some of Sydney’s nightclubs; and Neil Bodycote’s team put down a few schooners with Zane Frazier, whom he replaced in the tournament, along with other members of Sperry’s entourage. There was a strong sense of kinship among men charting a new frontier.

“It was a very small world,” Shamrock said. “These are guys that you train with, live with, travel with. The Brazilian groups were always very welcoming and family-oriented, so when we met Mario, it was kind of the same vibe. Even though we were standing opposite each other, it just felt good. We were all doing the same thing. We’re in a foreign country doing our thing.”

Simon Sweet, Hiriwa Te Rangi, Carlson Gracie, Mario Sperry, Matt

Rocca and Vernon White after the tournament concluded. | Provided

by Matt Rocca

The morning after the event, Bable was up early arranging for fight purses to be paid via bank transfer from revenue the event had generated. Next came tearing down the infrastructure built inside the convention center. Lastly, he made sure he had all the footage of the spectacle ready for post-production.

Bable’s to-do list grew that Wednesday when SEG filed proceedings against him for trademark infringement, arguing he had passed off his promotion as the UFC and unlawfully used SEG’s logos and intellectual property.

Among other things, the lawsuit sought to temporarily restrain Bable from distributing the event on VHS (this, after he had already peddled pre-sale orders through Blitz magazine) and to prevent him from marketing the tournament and future events as the “Australasian UFC.” In addition, SEG sought damages with interest, compensation for legal costs, orders that Bable publish corrective advertising and orders that permanently prevented Bable from using an octagonal cage in future NHB events.

Ultimately, SEG appeared to lose interest in the lawsuit after Bable gave a legal undertaking to the Federal Court to change the name of the event to “Caged Combat 1” and include disclaimers stating it was not associated with or licensed by SEG. The release of the VHS was delayed some weeks as a result of the proceedings, but by mid-April, he was free to distribute it in hopes of making back at least some of the estimated $250,000 he invested in the tournament.

It was at this point that Bable believes he made a fatal error.

“I got a deal,” Bable said. “Lionsgate Films picked up the rights to actually distribute it, as did Warner Bros. Lionsgate bought it and shelved it, for whatever reason. I think that may have had something to do with the SEG. When I followed up and asked, ‘Why isn’t this happening?’ The response I got was that they wanted to promote the UFC brand and shelve my VHS because they wanted to invest in the UFC. They wanted to buy the rights to distribute in this area.”

That left Time Warner as an option, according to Bable, but it was not meant to be. This was the moment that played a key role in the demise of his fight promotion and his decision to leave the industry.

“I had the music from the ‘Fever Girls,’ which we didn’t have the rights for,” Bable said. “The post-production guy said they could lay in some studio music. We could have done it right then. I said ‘hold on’ and called my copyright attorney. I explained the situation. We didn’t have rights to one of the songs; it was a Bon Jovi song from memory. I said that we could edit it out right now and asked what we should do. The advice was, ‘Don’t worry about it. It won’t be a problem.’ That advice totally killed everything that I did. The music rights stopped everything.

“We tried negotiations directly. They did as well with Bon Jovi,” he added. “We were negotiating and trying to get these rights, because we didn’t want to go back to post-production. And then it just ... it was an impasse. I think Time Warner actually sent me a letter saying if we couldn’t reach it by a certain time, they would have to drop it—and they did.”

Bable persisted with his original vision well into 1997. Full-page advertisements for “Caged Combat 2: The Rumble on the Reef” were placed in multiple issues of Blitz magazine published in the second half of the year.

A partial lineup of combatants included original tournament participants Chris Haseman and Elvis Sinosic, UFC veteran Paul Varelans, three-time Olympic wrestling alternate Tom Erikson and Australian Pancrase fighters Larry Papadopolous and Alex Cook.

The format was the same—an eight-man elimination tournament as the primary showcase—and two single-bout “superfights.” However, the planned event never came to fruition.

(+ Enlarge) | Blitz Magazine: Volume 11, Issue

9

An advertisement for “Caged Combat 2:

The Rumble in the Reef,” set to take

place near the Townsville Army Barracks

in Queensland on Sept. 27, 1997.

The fights took place on a rectangular canvas reminiscent of a traditional boxing ring but with chain-link fence instead of the ropes. Sinosic’s trainer, Anthony Lange, fought at the event and broke his arm after he fell back onto the chain link.

“Because the chain has no give, it’s basically a steel bar when it’s taut.” said Sinosic, who fought and won twice that night. “An interesting thing I heard through the grapevine, and I put this together after the event: Randy didn’t pay everyone. One of the [contractors] who wasn’t paid was [one of] the people who put the cage together. So for the Australasian Vale Tudo event, they didn’t have a cage.”

Though rumors swirled regarding Bable dishonoring his contracts with suppliers, only one, referee Cameron Quinn, confirmed being stiffed.

“Tell Bable he still owes me $300,” Quinn said.

Bable denied that he left any contractor high and dry.

“Everybody got paid,” he responded. “Although there were a few people that probably took longer to get paid than they should have.”

There’s little doubt that finances were a big reason why he downgraded for the AVT event and left the industry all together soon after.

Bable’s contribution, short lived as it was, was nonetheless important to the people who shared the experience.

Michael Schiavello got his start in MMA commentary thanks to Bable.

“I had one in the books. I had done a solid job. I had a calling card. I would go on to commentate MMA events worldwide and work on the big promotions such as Strikeforce and Dream and Dynamite and One Championship,” Schiavello said. “It all began with Caged Combat, and I will forever be grateful for Randy Bable giving a 22-year-old an opportunity to commentate a major event in the history of Australian martial arts.”

Chris Haseman and Elvis Sinosic, virtual unknowns in 1997, received significantly greater exposure on the international stage from the event. Sinosic took Frank Shamrock to a decision at the K-1 Grand Prix 2000 Final event three years later, then made his way into the UFC, where he fought for the 205-pound title against Tito Ortiz. Haseman would fight his next 25 fights for Japan’s Rings organization, culminating in a bout with Fedor Emelianenko in 2002.

Even controversy from their fight served to be a positive for the pair. Sinosic criticized Haseman for his alleged dirty tactics, cementing a rivalry that bubbled in the background while they represented Australia on the international circuit. Some 13 years after their first meeting, the UFC touched down in Australia for the first time with UFC 110 at Sydney’s Acer Arena, and a rematch was booked for the two past-their-prime pioneers. The fight would ultimately fall through—Sinosic was forced out with a shoulder injury, and Haseman was removed from the card—but the spotlight certainly did not hurt them as they transitioned into retirement.

(+ Enlarge) | Photo Courtesy: Elvis Sinosic

Neil Bodycote, Mario Sperry and Elvis

Sinosic, all smiles during Sperry’s

BJJ seminar in Sydney.

Vernon White claims his participation in the “rip-off” UFC event led to SEG refusing to work with him, though he eventually signed with the promotion after it had been purchased by Zuffa in the early 2000s. Matt Rocca, whose debut fight against Sinosic lasted all of 41 seconds, also had a tough time returning to the Lion’s Den and departed the academy soon after.

“I was a disaster,” Rocca said of the aftermath of his trip to Australia. “Keep in mind that this was an extremely successful team. They’re all alphas. If you do well, you’ll get the accolades. If you don’t, you’ll hear about it. That wore on me. Although I had competed, I didn’t make that transition from young boy to fighter.”

Rocca returned home to Canada, dejected with his performance, holding onto the sense that the MMA industry was not going to “take flight.” Time spent away from the fight game made the 20-year-old reconsider what he wanted to do with his life. He had a revelation: “Maybe this was not what I was destined to do.” Rocca listened to his parents, who advised him to go to school. Today he is a police officer in Ontario, Canada.

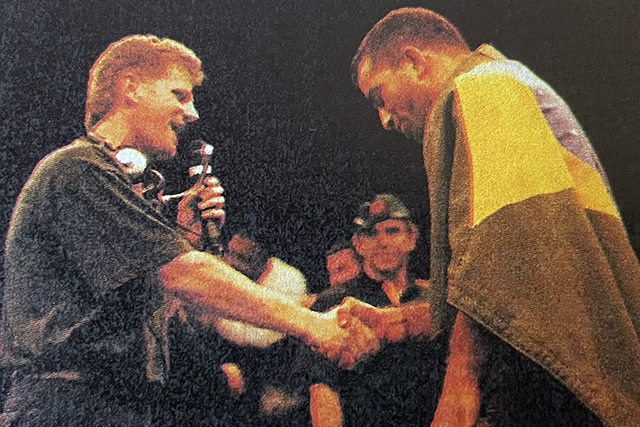

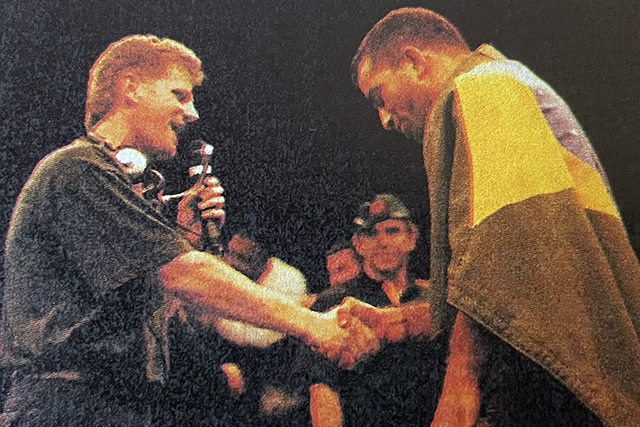

Randy Bable congratulated Mario Sperry on winning the

“Australasian Ultimate Fighting Championship.” From Blitz Magazine,

Volume 11, Issue 5.

Perspectives differ on what impact, if any, that Bable and his short-lived promotion had on mixed martial arts, in general, and on Australian MMA, in particular.

For his part, Bable likes to think the scale and professionalism of his spectacle on March 22, 1997 set a high-water mark for NHB at the time and played a part in propelling the sport into the multibillion-dollar industry it is today. Others lament that the promotion was too ahead of its time to meaningfully influence the trajectory of NHB, which was about to disappear from cable television in the United States and spend years languishing in relative obscurity outside of Japan.

The dearth of major events in Australia until the real UFC touched down in 2010 supports the latter interpretation of history. Though small promotions, including incarnations of Pancrase and Rings, tried cultivating a market for mixed fighting in Australia in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was not until later that a reliable regional scene established itself. This was followed by a trickle of Australian fighters into the UFC and other organizations—“The Ultimate Fighter” Season 6 semifinalist George Sotiropoulos and Bellator MMA middleweight champion Hector Lombard were among them—but the region’s talent did not explode until the UFC targeted Australia for regular events, including with its biggest stars, and a handful of seasons of “The Ultimate Fighter.”

Australia and New Zealand have since produced contenders across multiple divisions and crowned three UFC champions: Robert Whittaker, Alexander Volkanovski and Israel Adesanya. Australian crowds twice set the attendance records for UFC events—first at UFC 157, where Holly Holm shocked the world by knocking out the seemingly indestructible Ronda Rousey with a second-round head kick, and next at UFC 243, where Adesanya, the current 185-pound champion, commenced his championship run with a stunning knockout of Whittaker. Australia is frequently cited as the UFC’s biggest per-capita PPV domain, and ever more Australian fighters and organizations are being brought within the promotion’s orbit.

How much credit Bable deserves is a matter for debate.

“I just ran out of steam,” Bable said. “You look at the event and everything that happened. Everyone—everyone—tried to stop me. I was up against the wall every direction I went. The police, the boxing commission, the local government. The venues didn’t want us, the sponsors didn’t want us. In the end, we made a great product, but everybody tried to stop us. I got beat down for a year, then took a bath on the income, as well. I had to recover from that.

“I basically just got back to work,” he added. “I was a commercial builder, so I went back to putting together contracts. I fortunately had the ability to do that, but it took a little while to recover. I had a wife and two little kids, remember. If I was a single man, it might have been a different story, but my family was my top priority.”

Aware of the opportunity he had in 1997 to impact the direction of MMA, Bable thinks about what could have happened if not for a few bad calls—with Renee Rivkin or the distribution deal with Time Warner.

“It would have changed the course of my life,” he said. “It tormented the hell out of me for five years, you know?”

Bable was coy when asked if he was completely over MMA. He wrote a screenplay inspired by the March 1997 event and plans on releasing the second vale tudo event at some point. The raw footage is gathering dust in the Tennessee home where he currently lives with his wife.

Jacob Debets is a lawyer and writer from Melbourne, Australia. He is currently writing a book analyzing the economics and politics of the MMA industry. You can view more of his writing at jacobdebets.com.

Related Articles